Libstl provides basic functions for reading STL files, but instead of providing just a parsing function, libstl includes easy to use functions to build more meaningful data structures from the raw triangle data.

- It is small and fast, suitable for embedded systems,

- increasingly well documented (keep reading),

- un-opinionated and easy to extend,

- returns an indexed triangle mesh,

- can compute half-edge or quad-edge data structures,

- supports 15-bit triangle colors,

- treats concatenation of multiple STL files as a polyhedral complex

- keep calling

loadstl()until it fails, - comment field defines per polyhedron attributes,

- simplest data format for defining multi-material 3d prints

- keep calling

Repairing STL files is not one of the goals of libstl, because that would require subjectively changing the input geometry and the topology it implies. Instead, from libstl point of view, an application for repairing STL files would probably benefit from using it.

Below is an example program for loading a file and computing half-edges and dual-edges for it.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include "stlfile.h"

int main(void){

char comment[80];

FILE *fp;

float *vertpos;

triangle_t *tris, ntris;

vertex_t nverts;

uint16_t *triattrs;

fp = fopen("path/to/file.stl", "rb");

loadstl(fp, comment, &vertpos, &nverts, &tris, &triattrs, &ntris);

fclose(fp);

halfedge_t *fnext, *vnext, nedges;

vertex_t *evert;

halfedges(tris, ntris, &fnext, &evert, &nedges);

dualedges(fnext, nedges, &vnext);

return 0;

}

There are three basic data types: a vertex, a triangle and a half-edge. All of them are unsigned integers, and each represents a unique identifier for an object of the said type. We intentionally define them as abstract identifiers for the types, to separate the algorithm specific details of what it means to be a vertex, a triangle or a half-edge, from the object itself.

Unique identifiers start from 0 and increase sequentially. ~0 (the binary complement of 0) is used as an invalid identifier where necessary. Every type has its own identifier space starting from 0, and functions don't typically return an array of the identifiers themselves, but instead return how many vertices, triangles or edges there are.

Vertex positions are stored as an array of floats, and a coordinate of a vertex can be accessed by indexing the position array with the vertex itself. As a technical detail, the identifier may sometimes need to be scaled when accessing an array, like in the example below, where the coordinate array has 3 floats per vertex (x, y and z).

x = vertpos[3*vert];

y = vertpos[3*vert+1];

z = vertpos[3*vert+2];

If the vertpos array consisted of structs with x, y and z fields, the multiplication would not be necessary. However, using flat arrays like above makes it easier to tell OpenGL where and how to fetch vertex data.

It would be nice to get type errors for things like trying to use a vertex to index a half-edges attribute array, but the type system of standard C is too weak to express that.

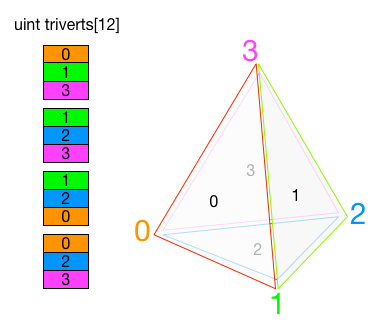

The loadstl function in libstl return an indexed triangle mesh, where vertex position data is in one array, with duplicates merged, and a triverts array, where a groups of three vertices express the corners of individual triangles.

As discussed in the previous section, only the number of vertices and triangles is returned to indicate what identifiers were used.

int loadstl(

FILE *fp, // file to read STL data from

char *comment, // 80-byte buffer to store the STL comment to

float **vertposp, // where to store the vertex position array

vertex_t *nvertp, // where to store the number of vertices

vertex_t **trivertp, // where to store the triangle corner vertices

uint16_t **attrp, // where to store the triangle attributes

triangle_t *ntrip // where to store the number of triangles

);

In the figure above, the small black numbers correspond to the triangles, and due to not having declared a struct for the triangle, the triangle needs to be scaled by 3 when accessing the triverts array, as follows

v0 = triverts[3*tri];

v1 = triverts[3*tri+1];

v2 = triverts[3*tri+2];

This is a relatively common way to present indexed triangle meshes to OpenGL, so we are showing that instead of declaring a per-triangle struct, which might make more sense from a readability standpoint.

Often applications find that they need to duplicate some of the vertices, because they differ in some other attribute than the position. Libstl is mostly concerned with topology defined by position sharing, and leaves the details of vertex duplication to applications.

A half-edge data structure consists of directed edges, conventionally looping counterclockwise around faces when looking from the outside in. A half-edge typically has at least the following properties

- a source vertex,

- a next half-edge (around left face when looking toward destination from the source), and

- an adjacent half-edge (opposite direction, loops around adjacent face).

In a well-formed triangle mesh (orientable 2-manifold), there are no orphan half-edges, which simply tells us that there are no cracks or holes in the surface and that every vertex (and edge) takes part in only one polyhedron.

Libstl takes the view that a single STL file should define a single solid object, with polyhedral complexes represented as a concatenation of multiple STL files. As such, using half-edges to represent connectivity in an individual STL files should not be an issue even for multi-material applications.

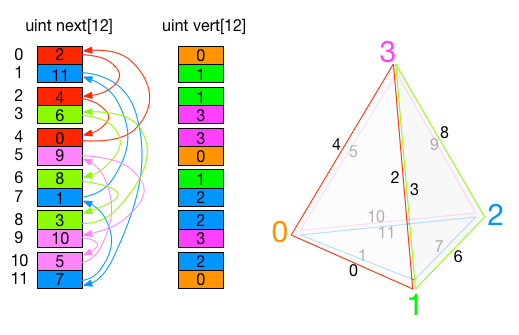

In libstl, half-edges are created in pairs so that accessing the adjacent half-edge is achieved by flipping the least significant bit of the half-edge, ie. edge^1.

int halfedges(

vertex_t *triverts, // triangle corner vertices

triangle_t ntris, // number of triangles

halfedge_t **nextp, // where to store the half-edges

vertex_t **vertp, // where to store the half-edge source vertices

halfedge_t *nedgep // where to store the number of half-edges

);

The figure above illustrates this principle. The next array contains loops around the faces of the mesh. At every index, the next array contains the following half-edge. Likewise, the vert array contains a vertex identifier corresponding to the source of each half-edge.

As an example, vert[edge] returns the source vertex of an edge, while vert[edge^1] returns the source vertex of the opposing edge (aka. the destination of current edge). As a more complicated example, looping around edges of a face can be written as follows.

uint start;

start = edge;

do {

edge = next[edge];

} while(edge != start);

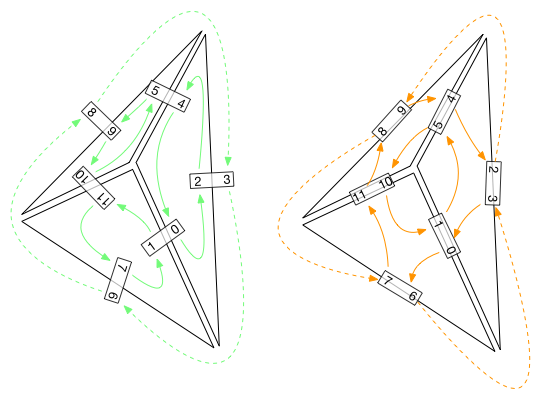

The dualedges function computes a dual of the half-edge next graph, with edge loops going around vertices if face-loops were passed, and vice versa. Quad-edges can be quite naturally represented as two separate next arrays indexed by the half-edges, say fnext and vnext, corresponding to next around the right face and next around source vertex respectively. This way the dual graph can be passed to a function by simply calling it with the fnext and vnext arguments swapped.

The left illustration above shows the face loop half-edge topology, with the array indices in numbers and the next array values as green arrows. In a similar manner, the right illustration shows the vertex loop topology computed by dualedges.

int dualedges(

halfedge_t *fnext, // primal half-edge graph (face loops)

halfedge_t nedges, // number of half-edges in primal graph

halfedge_t **vnextp // where to store the dual graph (vertex loops)

);

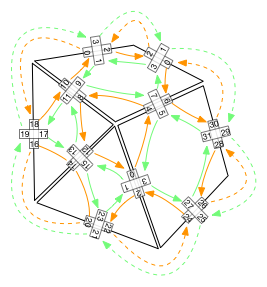

The conventional quad-edge consists of four next pointers, where each pointer participates in a list of edges around a geometric entity.

Two of the pointers in a quad-edge correspond to the next array in half-edges. The remaining two correspond to next arrays on the dual graph, where outgoing edges from a vertex are chained together in a counter-clockwise direction.

The navigation operations of the traditional quad-edge data structure are the same as those in the half-edge data structure, with the addition of a rotate operation, which moves between the face-loop and edge-loop graphs.

Merging the two arrays to form a standard quad-edge is not very difficult either, giving a structure where a full edge is a set of four consecutive integers and slightly different arithmetic from the half-edges.

STL files are the format almost everyone loves to hate, because it is perceived as wasteful and because it does not carry connectivity or other application specific information, with the exception of a rarely implemented color encoding extension.

After a long time of whining about the badness of STL and dealing with geometry of various kinds, we are humbled to admit that STL files are in fact a reasonable format for storing and transferring piecewise linear geometry.

We have found that most of the characteristics of indexed encodings don't turn out to be so great in practice.

- General purpose compression algorithms (like gzip) typically compress an STL file to the same size they compress indexed encodings of the same mesh to: they are designed to exploit repetition of various kinds.

- If geometry makes sense in an indexed format, it also makes sense as an STL file.

- Bad geometry is a problem in indexed formats too, and needs to be repaired.

- Rendering applications need duplicate vertices at texture seams for example, so indexed meshes written by such applications tend to have intentionally broken topologies.

- Multiple STL files can be simply concatenated together to represent polyhedral complexes, extending standard STL to volumetric applications and beyond.

So, while everyone will surely continue to hate STL, it is the least common denominator, and for a wide range of applications the competition offers no substantial upside.